When Parliament Speaks and the Presidency Stays Silent

Somalia’s 2018 ban on DP World remains unenforced, as two

administrations have bypassed constitutional procedures.

In 2018, Somalia’s Federal Parliament passed a resolution to ban DP

World from operating within Somali territory. Lawmakers argued that the

company’s agreements with regional administrations violated Somalia’s

Constitution, which gives the Federal Government exclusive authority over

foreign affairs.

The resolution passed with a clear majority in the House of the People,

but it was never enacted. Under Article 90 of the Provisional Constitution, a

resolution passed by Parliament must be signed by the President to become

legally binding. Then, President Mohamed Abdullahi Farmaajo did not sign it. As

a result, the resolution was left inactive.

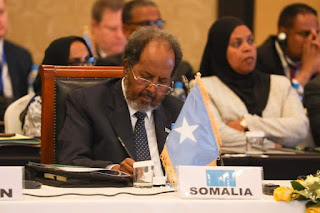

When President Hassan Sheikh Mohamud returned to office in 2022, the

same resolution remained pending. Despite holding the constitutional authority

to approve or reject it, he took no action. The ban was neither enforced nor

challenged. During this period, DP World continued its operations in Somali

ports, including Berbera, Bosaso, and Kismayo.

Although the 2018 resolution remained unsigned, the administration of

President Hassan Sheikh entered into new agreements with the United Arab

Emirates. These agreements were signed without being submitted to Parliament

for ratification, as required by Articles 69 and 90 of the Constitution. Unlike

during Farmaajo’s term, when no such federal agreements were signed, this

marked a direct procedural breach under the current administration.

This dual-track approach, which ignores a previously adopted resolution

while signing new, unratified agreements, has raised legal and constitutional

concerns. The government’s justification for cancelling regional contracts on

12 January 2026 was grounded in Article 54, which provides that foreign affairs

fall solely within the jurisdiction of the Federal Government. Yet the same

standard was not applied to agreements made by the executive branch.

Legal experts agree that the issue is not a lack of legal clarity. The

Constitution is explicit about how international agreements must be handled. It

is the consistent failure to follow these procedures that has undermined

institutional legitimacy.

“This is not a grey area,” said one constitutional law professor based

in Mogadishu. “Parliament acted. The executive branch, under two

administrations, failed to respond. That is a breakdown in constitutional

order.”

The government’s January 2026 directive to annul all agreements between FGS,

federal member states and the UAE was framed as a defence of national

sovereignty. However, the delay in acting, combined with the executive’s procedural

violations, has prompted criticism of selective enforcement.

Somalia’s constitutional system is built on shared powers and checks and

balances. When one branch of government performs its role while another refuses

to act, it creates an imbalance that weakens the entire system. The failure to

act on Parliament’s resolution, and the decision to sign new agreements without

following constitutional procedures, have contributed to that erosion.

As a Somali legal expert, I see this not only as a legal failure but

also as a governance issue. The Constitution must be followed in both letter

and spirit. When a president, in this case President Hassan Sheikh Mohamud,

fails to enforce parliamentary decisions and does not subject his own

agreements to the required legal review, it raises a deeper question: how can

the public trust a leadership that does not follow the rules it is sworn to

uphold?

The Constitution is not optional. Respect for its procedures is the

foundation of state legitimacy. When that respect is absent, so is the

authority it is meant to protect.

Comments

Post a Comment